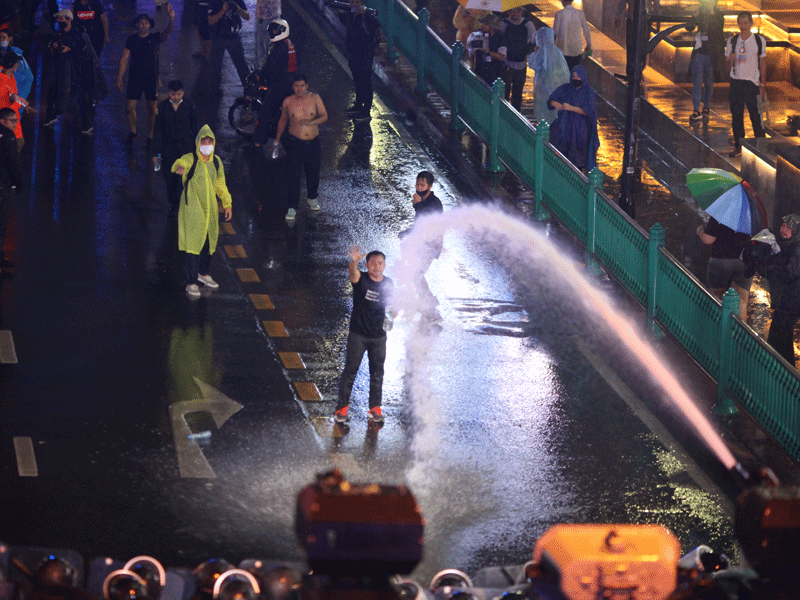

Before he put his helmet on and grabbed his camera,

Kan Sangtong, a former lecturer and political scientist, was a protester himself. Now 34, Kan no longer continues his political activism on the ground—he does it by capturing the fight for democracy in photographs. We talked to him about covering the protests, freedom of speech, and human rights in Thailand.

What made you interested in protest photography?

Like other freelancers, I began by shooting wedding and graduation ceremonies. But I didn’t feel like that was really for me, so I kept searching. After getting my masters in political science from Chulalongkorn University, I applied for a position at Amnesty International Thailand. I didn’t get the job, but the person who interviewed me offered me another position as a human rights observer for the Mob Data Thailand Project [a collaboration project between Amnesty Thailand and iLaw]. It was there that I received training to start reporting on political protests. At first, I had to submit a report and take photos of the protests. After seeing my work, they said I no longer needed to write; just taking shots was fine.

Guide us through your work process.

Amnesty Thailand is concerned for our safety, so we need to have protective gear before entering high-risk zones. If headquarters [Mob Data Thailand] tell you to retreat, you retreat. During training, they told us that if we’re taken in by the police, all we have to do is confirm our status as human rights observers. If there are any charges against us, they’ll take responsibility for them. They always insist that we don’t have to go to the frontlines. They don’t want “nice” shots. They only want to know what’s happening on the scene, or if police have really violated protesters’ rights. “Just bring yourself back in one piece. Your life is more important,” they say.

Have you ever refused to retreat, though?

Several times. On these occasions, my boss has asked me to join up with bigger newsgroups like Prachathai and Voice TV. Once the situation calms down, they tell me to retreat right away.

How do the police treat journalists in the field?

From the government’s perspective, there are two types of journalists: one they recognize, and the other that they don’t. In their eyes, to be fully recognized as a journalist, you need to receive a permit from the Public Relations Department and the Thai Journalist Association. This means you have to work for authorized news publications, either in Thailand or from other countries. Things, however, get complicated when you’re a freelancer. Since they don’t have full-time contracts, or the publications they work for may not be registered in the system, freelancers usually get into trouble with Thai police. There are also YouTubers and influencers who report on the scene. Some will shout stuff at the police while livestreaming, and the police usually exploit that and crack down on them, saying they can’t distinguish them from protesters. Some reporters don’t like these freelancers to be there—they think they only provoke the police.

Thailand has a journalists association. Do they protect freedom of press?

They are mostly conservative. Despite how the media has changed over the years, they still embrace old views of what they think journalists should be. But literally anyone can become a journalist. You don’t have to have a full-time job with a newspaper to call yourself a journalist. By creating a barrier to entry for new or independent reporters, they are giving the police license to violate the rights of people who are trying to do their jobs. In the majority of cases, the Thai journalist association sides with the government. They usually blame us for not following laws. They tell us we should return home before curfew [even if the protests continue]. We need to question why they never protect us.

Tell us about one of the most powerful shots you’ve taken at the protests.

I don’t think any of my particular shots are powerful. I just take shots of the situation at hand. But they represent only a moment frozen in time, and more often than not they allow people to interpret them however they see fit. A few weeks ago, I photographed a young protester who took out a gun and shot it one time. No one was injured. However, a [pro-establishment] Twitter user stole my picture and posted it with the caption: “Protesters turned violent, they had guns.” These moments can unfold into countless versions of reality if you let them.

Have you ever been caught in the crossfire at the protests?

I was hit by protesters’ flash bangs, once. I talked to one of the kids at a protest in Din Daeng recently. He told me they manufacture these themselves. They combine gunpowder, pebbles, nails, and glass and then wrap it all with red tape. They showed me how it worked. When they hit the ground, they send a small shockwave.

What do you think about the way the mainstream media portrays the protests?

Violence is something that both sides can exploit. The government and other pro-establishment parties can use it to portray demonstrators as aggressive and violent, and the media can intensify the moment and make the general public forget what the protests are really about.

For protesters, police brutality can serve as a way to prove to the world that the police aren’t complying with international laws, that the government and police are responsible for our suffering, that they are taking away our human rights. I understand that peaceful protests may not be the answer for everyone, and people have their own ways of expressing their anger, like what is happening in Din Daeng. Yes, the primary goals of the protest might be overshadowed by violence, but we can’t be so quick to judge which methods are effective.

Images courtesy of Kan Sangtong.